Submitted by Pielow Prescille, of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Pictured above: a De Havilland DHC-2 Beaver papercraft model, submitted by Pielow Prescille.

Submitted by Robert Munro, of Elliot Lake, Ontario.

Flew the Beaver in 1972 for Kyro’s Albany River Airways. 1974 For Athabasca Airways in Buffalo Narrows, Saskatchewan. In 1982 for Nakina outpost Camps in Geraldton, Ontario. CF-OCZ. CF-JKG. CF-BPC. I am a retired Air Canada Captain, 70 years old. [The Beaver is] a great aircraft [and] a dream to fly.

Submitted by Judy Murdoch, from Aurora, Ontario, Canada

James W. Keenan, who went by Jim, was born and raised in Latchford, Ontario and educated as a Professional Forester at the University of Toronto. He spent most of his career in the Department of Lands and Forests/Ministry of Natural Resources, living and working in the communities of Kenora, Pembroke, Tweed, and finally Toronto.

In Toronto, much of his career was spent in the Parks Branch. He developed the first Parks Classification system, the foundation of which is still used today and has been adopted by Parks organizations near and far. He served as Executive Director of both the Parks and the Lands and Waters Branches and later became an Assistant Deputy Minister with the Ministry of Natural Resources. His next steps took him away from MNR to the Management Board of Cabinet (Ontario) as Assistant Secretary.

He received what he considered the telephone call from the Premier’s Secretary of Cabinet in September of 1984 asking if he would be interested in becoming Deputy Minster of Correctional Services. Of course, he said yes! He ultimately retired in 1989 as the Deputy Minister of the Ministry of Tourism and Recreation.

Many many days in Jim’s MNR career saw him boarding one or another of the Beavers and Otters in the Ministry’s fleet of bush planes. Working in Kenora as a Timber Management Forester he did a lot of flying using L&F (Dept. of Lands & Forests) piston Beavers. This resulted in some interesting events.

“I recall flying south over the Lake of the Woods with a pilot who was just about to retire,” he said. “His eyesight was not too good and he wore glasses which he usually took off after we were in the air. He also was inclined to be forgetful. In any event, we’re flying along about 3,000′ enjoying the beautiful day when suddenly the engine stopped. Well now, you’ve never heard “quiet” until you hear the engine stop when you are flying. The pilot frantically tried to find his glasses, which he finally did – we are all the while coasting earthward – and a quick inspection of his instruments showed that we were out of fuel. He had forgotten to switch fuel tanks. He quickly did so and, after some coughing and spitting the engine finally caught again. While exciting?? we were not really in danger because the Beaver could coast to a safe landing as long as there was water below!”

Another adventure he recalled involved a trip into Shoal Lake, which runs off the northwest corner of the Lake of the Woods. “When we landed we got stuck in the slush. (Under heavy snow cover the weight of the snow depresses the ice and forces water up through the cracks to form slush. It’s really like getting a vehicle stuck in mud. With the Beaver, the skis sunk into the slush and the plane, once stopped, couldn’t move. Regardless of our trip purpose (to inspect some logging operations) we couldn’t get at it until we could free the plane. So we trudged the ¼ mile or so to shore and cut quantities of small poles which then, with the skis jacked up, we put under the skis and ahead of the plane to provide a “runway” of sorts. Unfortunately, every time the plane tried to rev up and take off, it would plunk down off the end of the runway. In the meantime we were behind the Beaver trying to push it. What happens then is that the slipstream of the plane blasts you and, at least once on my case, caught my snowshoes and sent me head over heels backwards. In the final analysis we decided to jack up the plane and leave it sitting on the runway of poles for an early morning try the next day when the overnight temperatures had frozen the top of the slush. We then hiked a few miles to a Mennonite logging camp (which was actually in Manitoba) where they fed us and transported us out to Hawk Lake on Highway 17, where we caught a bus back to Kenora. The pilot got a lift out to the plane via another L&F Beaver the next morning and got the plane off without further mishap.”

By the time Jim retired, he was flying in commercial aircraft rather than bush planes, but he would certainly be the first to say that flying in those earlier days was a heck-of-a-lot more fun and interesting!

Submitted by Jvan Aeberli (co-credit to Anna Maag), from Eglisau, Zurich, Switzerland

*that was in the year 1990 – still in the pre-GPS time!

The only alternative to a transatlantic flight was transporting in a 40-foot container. However, we did not want our newly restored Beaver to be dismantled and rebuilt by a specialist company. In addition, the thought of having crossed the Atlantic in a single engine at least once in our lives appealed to us more and more.

The decision was already made when we ordered our De Havilland: we — Anna Maag, Marco Montanari, Werner Röschlau and myself — will fly the Beaver from Seattle, WA to Switzerland. We are all in possession of a pilot’s license, although with different levels of experience. Werner is a flight instructor and airline pilot with over 7000 flying hours.

The whole rebuild work at Kenmore Air Seattle on our Beaver ordered on 30.9.89 — hence the registration N930AJ — took over nine months, so we had plenty of time for the preparation work. But how does the planning of such a big, adventurous trip work out?

A valuable and professional guide for a transatlantic crossing was given to us in the Stafford-Ivanovic transatlantic seminar in St. Moritz, Switzerland, which we attended in winter. Here one learns from competent ferry pilots what is important.

The preparations could be divided into the following parts:

– Equipment of the airplane

– Chart material, AIP/Jeppesen Trip Kit

– Technical knowledge and emergency procedures

– Route preparation

We were fortunate to have Werner Röschlau, a professional pilot friend, with his vast experience to assist us and also accompany us on the actual flight. Several factors influence the success of such a trip, especially the meteorological conditions that can cause a failure. That is why we chose the high summertime of August for the transatlantic flight. The pressure of deadlines can also be dangerous, you have to take your time and not want to be home on a certain date.

After an exciting crossing of the American continent over mountains and endless agricultural areas, we now fly along the great lakes, over the obligatory Niagara Falls, a thousand feet above the St. Lawrence River from Toronto, Ontario to Montreal, Quebec, up to Moncton, New Brunswick.

Here we are registered for the transatlantic check required by the Canadian Government. The aircraft’s navigational equipment is inspected, the emergency equipment is checked and the expertise of the PIC in charge is verified.

The Canadian authorities (Transport Canada) have only recently made this Moncton test mandatory because simply too many crews have been lost. The control in Moncton is not at all harassing but on the contrary very cooperative, helpful and supportive.

Our controller, himself a passionate DC-3 pilot for Transport Canada, takes great pleasure in our well-equipped Beaver shining in the evening light. But of course at that time no GPS on board — just standard IFR equipment and a short wave radio.

With the good feeling to have prepared everything correctly and competently, we fly in the most beautiful evening atmosphere the same day from Moncton to Goose Bay also called Happy Valley – however, we do not see a happy valley anywhere after arrival – the last stop on the American continent.

Soon it becomes night, and we can only guess the beginning of loneliness below us. Along the St Lawrence Gulf, over Anticosti-Island we take a direct course to Goose Bay. Only rarely a lonely light below us, the night is clear and cold. Around midnight we experience strange light phenomena: the aurora borealis*.

*Note from the dictionary

Aurora borealis (also called aurora), northern and southern light, a cold glow of the air on the night side of the earth, most often about 10° from the geomagnetic poles. The height of the aurora is 100-120km, but also up to 80km resp. 1200km. The aurora is caused by currents of electrically charged particles emanating from the Sun and deflected in the Earth’s magnetic field, which excites molecules and atoms to glow when they enter the atmosphere. The aurora is observed in a wide variety of forms: Arcs, bands, curtains, clouds, and rays. The luminosity is often variable, irregular or pulsating. Colour: mostly yellowish green but also red or blue to grayish violet.

We are fascinated by this celestial phenomenon! In front of us on the horizon is a twitching band, more luminous and eerie than our weather glow, which we can often observe in summer. The dimensions are imposing, one has the subjective feeling that the whole northern hemisphere is illuminated by the twitching light.

At 01:10 local time we land in Goose Bay, a strange atmosphere welcomes us to this large military airfield. US Army planes, which are on their way to the Persian Gulf (Kuwait war), are taking off and landing non-stop. We are in the middle of August 1990, and big B52 bombers and other fighter planes are shaking our already not quite calm, last night before the first big oversea water leg.

We then also learn a very strange story that had happened immediately before: on the runway aircraft parts were found that could not be identified. No aircraft could be identified which had lost these sheet metal parts. Apparently, a crew was travelling with an aircraft that had lost a piece of the outer skin.

Early in the morning, we inquire about en-route weather to Narsarssuaq (South Greenland), a seven-and-a-half-hour flight east from Goose Bay. Not exactly rosy forecasts: a front from the north is approaching and will influence the weather for the next three or four days; at our planned flight level wind from NE with 10-15 knots. We decided together after detailed consultation to take off immediately. So, we fill up with fuel — but full to the brim (we had an extra fuel tank for four hours in the cabin) — and file the flight plan, jump into the rented survival suits and report «Ready for departure».

As the owner of the Beaver, I have the honour of flying the first leg. At 4000′ altitude, we fly over the uninhabited mainland towards the Labrador Sea. It is a thrilling feeling when we leave the coast and fly out into the open sea!

We are happy about the reliable humming of our Pratt + Whitney R985 nine-cylinder, no malfunction, all gauges in the green area, everything runs like clockwork. Fuel consumption is 18 gallons per hour. Our total fuel capacity, including the ferry cabin tank, is 177 US gallons, enough for 9 ½ hours of flying.

Our shortwave radio from YAESU type FT-757 GX2 proves excellent, we have mostly clear communication on the way with our low altitude no radio communication is possible unless you find a nice airliner which can then function as a relay station. A few times we make use of this possibility and always meet extremely friendly radio operators, who then also behave very helpfully and send our message, e.g., a position report without grumbling further into the æther.

Suddenly, the speed display collapses, 80, 70, no more display! After a few anxious seconds, we notice an icing of the pitot tube. Half so bad, «Pitot heat» on and the problem is solved. A later check of the wings, however, is not very reassuring: icing on the wing nose. Already 3-4 cm of ice can be seen from the comfortably heated cockpit, tendency increasing! Also, the struts and the landing gear are completely covered with ice. Snowfall has started, and the outside thermometer shows around zero degrees Celsius.

Our only chance to get rid of the annoying ice including the unpleasant feeling in the stomach area is a descent to 2000′ AMSL. Now we also see the sea surface more clearly. High foam-capped waves are coming from the north, and an infinite gray-blue depth makes our souls shudder. Down here we would simply be lost! We are glad not to be over the ice cap of Greenland now because then sinking into warmer air masses would not be possible!

After half an hour the ice has thawed (thank God), and we climb again to a reasonable altitude. Now it’s time for a fortifying snack! A few cheese sandwiches and some chocolate can taste wonderful! We turn on a classical CD on our intercom and enjoy the indescribable atmosphere on board. Everyone is busy with himself and the long way ahead of us. Our journey is an experience of the gigantic dimensions of our earth, a feeling that can never arise in a jet plane. But in a small airplane, which moves forward with 120KTS, is where one experiences how large the distances actually are.

After five more hours of flight, suddenly the NDB indicator moves, and we receive a signal on 265 kHz from Julianehaab, a radio beacon at the southwestern tip of Greenland. (60°70’North 46°10’West, variation 35° West).

Yippee, we are right on course! A small correction and we are heading straight for the middle of the three fjords off Narsarssuaq. But we have to be patient for another hour of flight until we turn into the actual fjord and make the last stretch to Narsarssuaq.

A severe headwind up to 30 KTS awaits us and extends our last leg. Approach and landing at BGBW work out fine. Relieved, tired and satisfied we climb out of our faithful ‘little Beaver’, as we tenderly call our flying machine. We even treat our DHC-2 to a 50-dollar parking place in the hangar of GROENLANDSFLY. In the only, yet cozy hotel we now must hold out for a few nights and days. The wind conditions are unfavourable and finally, we learned at our seminar that a ferry pilot should never accept a forecast headwind.

Daily extended walks to the icebergs, across barren meadows with actual mountain flora. Beautiful unknown loneliness after leaving the few houses around the airfield. From time to time, one finds remains from earlier times when the Americans during the second world war used this plot of earth and rubble.

Then on the fourth day of our stay, the wind forecasts are a bit better. We plan our leg to Reykjavik in such a way that if our groundspeed is insufficient, we could divert to Kulusuk (East Greenland) to refuel. To be honest, however, we are not very happy about refuelling in Kulusuk at a gallon price of 7 dollars, given our already strained wallet. Besides, it’s the weekend and landing costs a few hundred dollars extra!

The destination for the day is Reykjavik: an 8-hour flight first over the ice cap, then over drifting icebergs and the sea to the green island of Iceland. Our mood on board is excellent, and the snack tastes delicious. Cross bearings with NDB Kulusuk result in sufficient groundspeed so that we can continue on a direct route.

On the way, we have contact with several airliners, and fortunately, we encounter good en-route weather. An unbelievably colourful evening atmosphere with shining rainbows and a freshly washed atmosphere (the rain had just stopped) welcomes us to Iceland. We fly over the huge army airfield Keflavik and prepare to land in Reykjavik.

Now we’re already sniffing European air, although there’s still a nice bit to cover. We plan our next leg to the Faroe Islands and on to Norway. The following day, a refuelled Beaver greets us in bright sunlight. Our weather briefing assures us that we will encounter decent weather along the way. Along the south coast of Iceland, we enjoy the foreign landscape with its volcanic features. Again out into the open sea with course to Vagar/Färoer Island!

During 350 days a year, bad, rainy weather is supposed to prevail here on these sleepy islands. But when we arrive, the sun is shining and the lush meadows make us think of flower mats in our homeland.

The place is located behind a rock and is quite sloping. We are glad to have nice weather and thus a top view. Landing IFR here between the mountains does not seem very pleasant to us.

After a late lunch in a nearby restaurant, we learn that en-route to Norway the weather conditions are not the most optimal. The forecasts are even far less enticing. An immediate departure is in order. Now the transatlantic flight is already mentally behind us anyway. We want to get home as soon as possible, greet our friends, take care of the Beaver, be at home, and be happy about the good success.

On Friday we will introduce the Beaver to our new home and fly them over the Swiss mountains and passes to Birrfeld/LSZF for the first time. We receive a great welcome, dear friends together with our parents await us with champagne.

Truly it was an unforgettable experience! We happily completed our first transatlantic flight without any problems under the competent guidance of our friend Werner Röschlau after more than 71 flying hours. The common experience of such a journey connects us four friends especially. We trusted our flying machine, a ‘58 DHC-2, often affectionately called «Beaverli», completely. Perhaps that is why it has never let us down. It is now being treated and cared for in the best possible way.

Submitted by Gary Gentle, of Innisfil, Ontario, Canada

I am a hobby aircraft photographer in the Barrie area. I would like to submit these 8 of my favourite photographs that I took of CF-OBS for the 75th Anniversary of the Beaver!

Some of these photos were taken on the Saturday, at the Muskoka International Airshow and the water photos were taken at Lake St John the same weekend.

I had talked to OBS pilot Neil Ayers after the Saturday after his show performance, and he offered if I wanted to come to Lake St. John where OBS was parked. He would do a few water pick up and drops close to me when he was warming OBS up before the show. I took him up on his generous offer and got some amazing shots!

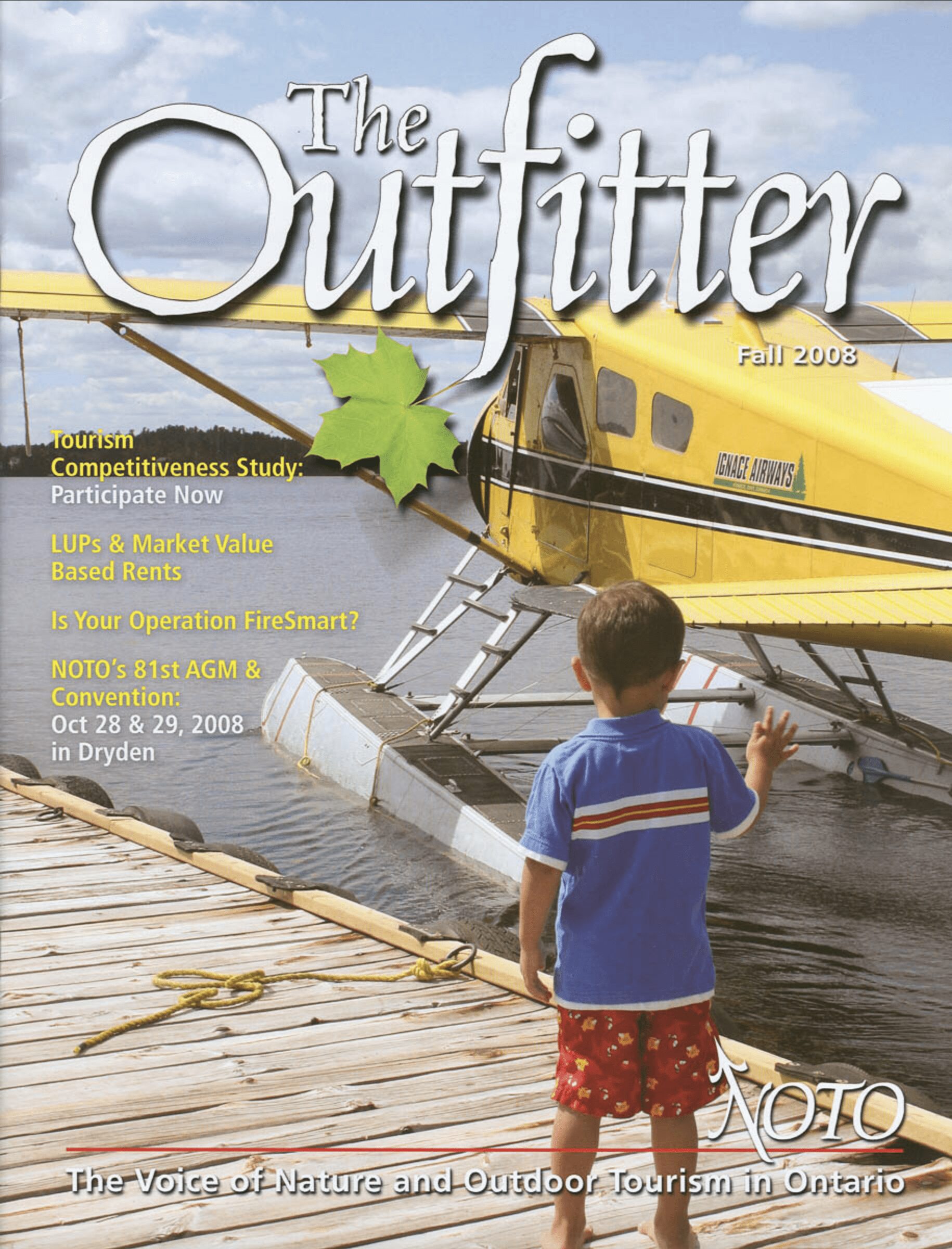

Submitted by Karen Greaves, of Ignace, Ontario, Canada

For more than three decades a bright yellow piston Beaver on floats was parked at my front door.

De Havilland (DHC-2) Beaver and I go way back, all the way to my arrival home, at birth, from the hospital. My parents were living right along the side of the de Havilland airport (Downsview) in Toronto. I had no idea until much later that C-GZBR was built there that year and likely took its first flight right outside my bedroom window!

Skip ahead 20 or so years to Thunder Bay where I married a young wanna be pilot. Brad soon began his career as a bush pilot and developed a love for the Beaver while flying the ruggedly designed aircraft in the rough Canadian Wilderness. Interestingly, the first Beaver he flew was C-GZBR, years before we owned it. After he gained experience over several years flying for various air carriers, we were fortunate to have the opportunity to enter the industry ourselves as operators. Before long we packed up the family (two toddlers in tow and a baby on the way) and moved to Ignace, Ontario.

With two other couples as partners through the late 80’s and 90’s we operated, among our sister companies a dozen bush planes, of which 9 were Beavers. One was an original 1947 Beaver C-FOBV (serial # 5)!

The Beaver played an important role in our growing family’s history. It seems to be prominently featured in the background of every family milestone photo from anniversaries to graduations to reunions to weddings. For 35 years at least one Beaver was parked at the dock in front of our house every day of the summer. In the winter the fleet was parked in the yard just meters from our doorstep patiently waiting their turn through the hangar for regular maintenance.

Each of our kids had many opportunities to sit up front with their dad. All three kids learned to pump floats, load the aircraft, fuel and oil them as well as clean them inside and out. They’ve been in the hangar handing parts and tools to the AMEs and helped dock the aircraft under windy conditions. They learned to dispatch and flight-follow the Beaver. They weighed countless loads and were able to remind new pilots of Beaver capabilities and share loading tips.

When our oldest daughter Krista was married, her desire was not to be brought to her wedding in a limo but instead in a Beaver. This was easily arranged. Her father taxied her down the lake to the beach side venue in Beaver ZBR.

After her wedding, Krista moved to the west coast and while searching for a job, decided her familiarity with Beavers necessitated a visit to a floatplane operator. She was thrilled to find ‘round nose’ Beavers amongst the shiny, pointy ones. She ultimately worked on the coast in the “Beaver business” with Harbour Air in Richmond until she moved back to Ontario a decade later.

Our youngest daughter Joanna, ever the adventurer, was often climbing into a vacant seat just for another ride on the durable aircraft. Her love of flying has translated into a career as a flight attendant with a major Canadian carrier.

The influence of this remarkable aircraft extended to our extended family. In 1990 Brad hired a pilot to fly a Beaver for the summer. By the end of the season, she was engaged to be married to Brad’s younger brother who also worked for us. One nephew who hung around the seaplane base helping load and dreaming of the day he could fly a Beaver ultimately pursued a career in aviation, which focused on the Beaver, Turbo Beaver and their big brother the Otter.

I have too many photos of DHC-2s to count; taken in every season, time of day, and change of weather. Many have been printed for sale and featured in aviation or tourism calendars and publications. One image was selected for the cover of “The Outfitter” magazine. It features our oldest grandson sending off ZBR figuratively saying good-bye to the summer season.

In 2019 we sold our business. I’m happy to have so many memories of that one special Beaver #1272, C-GZBR. Whenever I hear the distinctive rumble of a Wasp Junior overhead, I still pause and search the skies for my favourite aircraft.